The Republic of Malacandra

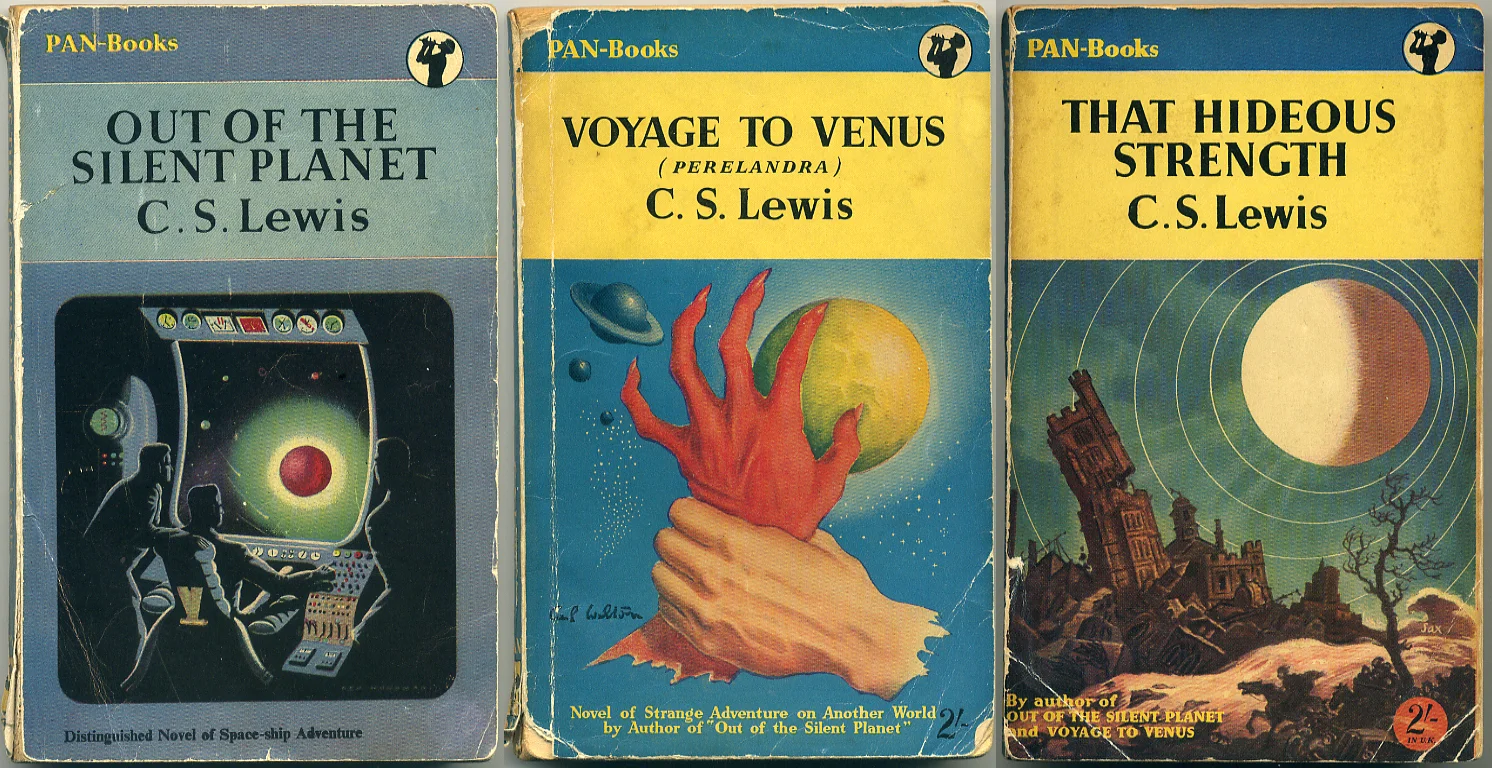

An avid reader and lover of tales, C.S. Lewis crafted worlds and stories full of borrowed imagery, characters, and plotlines. For example, Father Christmas makes his appearance in the Chronicles of Narnia, and Till We Have Faces is a re-telling of the Greek Psyche myth. Plato also appears to have left a mark on Lewis, warranting mention in a couple of his novels and, as I hope to exhibit, inspiring the world of Malacandra in Out of the Silent Planet, the Space Trilogy’s first volume. Malacandra bears remarkable resemblance to the ideal society Plato outlines in The Republic, a work known to C.S. Lewis.

Three classes arise in The Republic into which all people are placed at birth. One is either bronze (the artisan class), silver (the warrior class), or gold (the class of philosopher-kings). A democratic mind recoils, yet Plato is not advocating a strict caste system but rather an innate ability: a specific skill and a love for that skill within each individual. In Plato’s republic, every person is endowed with a natural talent, perfects that talent, and then spends all of life in skillful use of that talent. No one who is a blacksmith aspires to be a philosopher-king, just as no warrior yearns for the quiet of farm life. Every person is whom they ought to be, doing what they ought to do, and the ideal is reached.

So far, Plato’s ideal society is perhaps acceptable as an ideal. Then comes the analogy of the cave, so popular and yet so misrepresented in popular form. The philosopher-kings discover the “cave” for they are not only the rulers but also the intellectuals of the republic. Plato asserts that although the philosopher-kings uncover truth in the cave, in realizing that so many would not be able to understand or survive freedom into the light of truth, these philosopher-kings (or queens, as women were permitted to this class) become guardians of the cave, keepers of the chains. They condemn even themselves to the shadows rather than reality, for the sake of the ideal. This ideal then, which a mere moment earlier seems tolerable, is shown to have a terrible price, the price of truth.

Two things illuminate Lewis’ pilfering from Plato in Out of the Silent Planet: a cave scene, and a class structure. The end of the novel takes us to the city of Meldilorn. Here one encounters the interaction of Malacandra’s three types of hnau, or races: seroni, hrossa, and pfifltriggi. Each of these “classes,” if you will, is born into a specific station, spending their lives fulfilling the purpose for which they enter the world. Ransom, the traveler from Earth, learns this from the first pfifltrigg he meets. Asking whether all the pfifltriggi enjoy digging in the mines (the pfifltriggi are the miners and craftsmen of Malacandra), the pfifltrigg, Kanakaberaka replies, “All keep the mines open; it is a work to be shared. But each digs for himself the thing he wants for his work. What else would he do?” Each class of Malacandra knows the talent they possess and the goal they are to work toward – Plato’s republic come to life.

If Malacandra is Plato’s republic, where are the philosopher-kings, and do they in fact keep every other species in chains? The “cave scene” mentioned earlier plays out during Ransom’s first interaction with a sorn. On his journey to Meldilorn Ransom is told to go to the tower or Augray, a sorn who would help him. At the end of Ransom’s endurance he sees a light, and pushing himself toward the light finds a cavern lit by firelight.

“There were two things in it [the cavern]. One of them, dancing on the wall and roof, was the huge, angular shadow of a sorn; the other, crouched beneath it was the sorn himself.”

Such a picture seems directly copied from the pages of Plato: the shadow on the wall is Ransom’s understanding of the sorn, the cave is where Ransom encounters truth – the actual sorn being truth, and the knowledge gained releases Ransom from the fear that has enslaved him. Are then, the seroni equivalent to the philosopher-kings, and do they suppress the truth of the cave? Here is where Lewis breaks faith with Plato.

The truth Ransom finds is not controlled by the seroni, but instead leads him to the “ruler” of Malacandra – Oyarsa. Oyarsa uniquely fulfills Plato’s position of philosopher-king as Oyarsa is not a member of any Malacandrian race, nor, in fact, is he Malacandrian. Traces of The Republic, however, filter in with the history of Malacandra Oyarsa provides. Weston, also from Earth, explains to Oyarsa that the people of Earth have the ability to travel to Malacandra, to subdue it, and to rule it. Oyarsa admits this, and then questions why Weston is not curious that Malacandra, a planet older than Earth, has not sent its people to Earth to rule it. When Weston asserts the people of Malacandra have never had the ability, Oyarsa contradicts him. Malacandrans “were well able to have made sky-ships. By me [Oyarsa] Maledil stopped them. Some I cured, some I unbodied.” To maintain the ideal, the peace of Malacandra, Oyarsa prohibits certain knowledge.

Plato as the inspiration for Lewis’ Malacandrian society is perhaps hasty. Yet it appears that the peoples of Malacandra act as Plato’s classes would – content with their abilities and position. The leader (philosopher-king) of Malacandra possess the key to certain knowledge and determines how much of that knowledge is shared with the Malacandrian people. Malacandra and it’s people are entirely of Lewis’ imagining, as is the story of Ransom and his time there – it’s a great tale, one highly recommended. If curiosity about political philosophy also blossoms while reading Out of the Silent Planet, take a gander at Plato’s Republic. Perhaps C.S. Lewis meant for The Republic to stand as a prequel to the Space Trilogy!

[Editor's Note: This blog is a participant in #LewisWeek]