Liturgy Series: Part 2 – The Liturgical Calendar

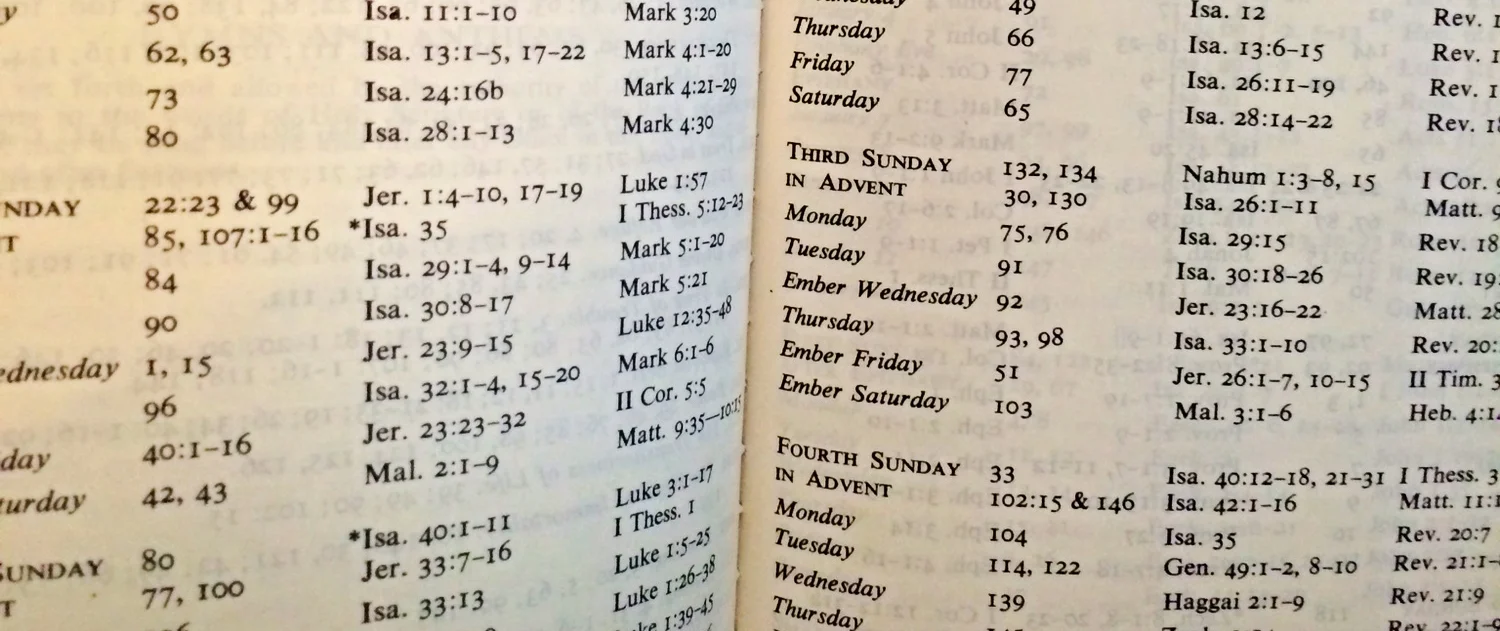

My Great grandfather's (Humphrey Finney) Book of Common Praryer

I grew up in the episcopal church. This meant that each year followed certain seasons in the liturgical calendar. Like most churches there were seasons for lent, easter, and advent. However, there were also other seasons in the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal church: Epiphany, Ascension and Trinity. While many churches and denominations scoff at the concept of a liturgical calendar it should be noted that despite their condescension you'd be hard pressed to find any church that doesn't recognize the seasons of Advent and Easter. Further, as I hope to show, the liturgical practices of the church at a macro-level (liturgical calendar) can serve as a powerful counter-formation to the cultural calendars that seem to dictate our lives at every turn.

As promised in Part 1 of this series, I will rely heavily on the work of James K.A. Smith, particularly (if not exclusively) his book Desiring the Kingdom. That being the case, let's go ahead and turn to Smith to drive home the reality of a church calendar serving as a counter-formation to the cultural calendars that are already embedded into the lives we lead:

If we read the practices of Christian worship, we would conclude that Christians are a people whose year doesn't simply map onto the calendar of the dominant culture. Tensions and differences will be felt differently in different cultures. (pg. 156)

Smith presents an important point about the concept of the church calendar in this quotation. The fact that Christians shape their calendars by seasons other than football season, summer vacation, winter break, etc. should serve as an important reminder that Jesus (not caesar, the mall, the football team) is Lord. Moreover, the liturgical practices of the church throughout the year will often be in tension with other dominant cultures.

One question that should be raised at this point is: Are American Christians the type of Christians whose yearly calendar is shaped more by the machinations of a godless culture or the Lord of all, Jesus Christ, and his body, the Church?

The Finney family Crest on first pages.

Having just seen that a liturgical calendar can serve as a powerful counter-formation to the yearly calendar of the dominant cultures we find ourselves in it also serves as a powerful eschatological reminder to the people of God. Smith makes the point that Christians should be a people who are oriented toward the future; people of expectancy. While the culture of the West emphasizes "living in the moment" the liturgical calendar of the church is constantly reorienting the people of God towards the kingdom of God which has both already arrived in Jesus and his Church and is still to arrive in its fullness. Each season of the liturgical calendar serves as a reminder to the people of God that the kingdom that they desire is yet to be fulfilled in the world they inhabit; the liturgical calendar serves as ballast for the ultimate desire of the Christian people. Smith uses the example of the season well to illustrate this point:

Advent shakes us out of the presentist complacency that we can be lulled into. Instead, we are called and formed to be a people of expectancy—looking for the coming (again) of the Messiah. (pg. 157)

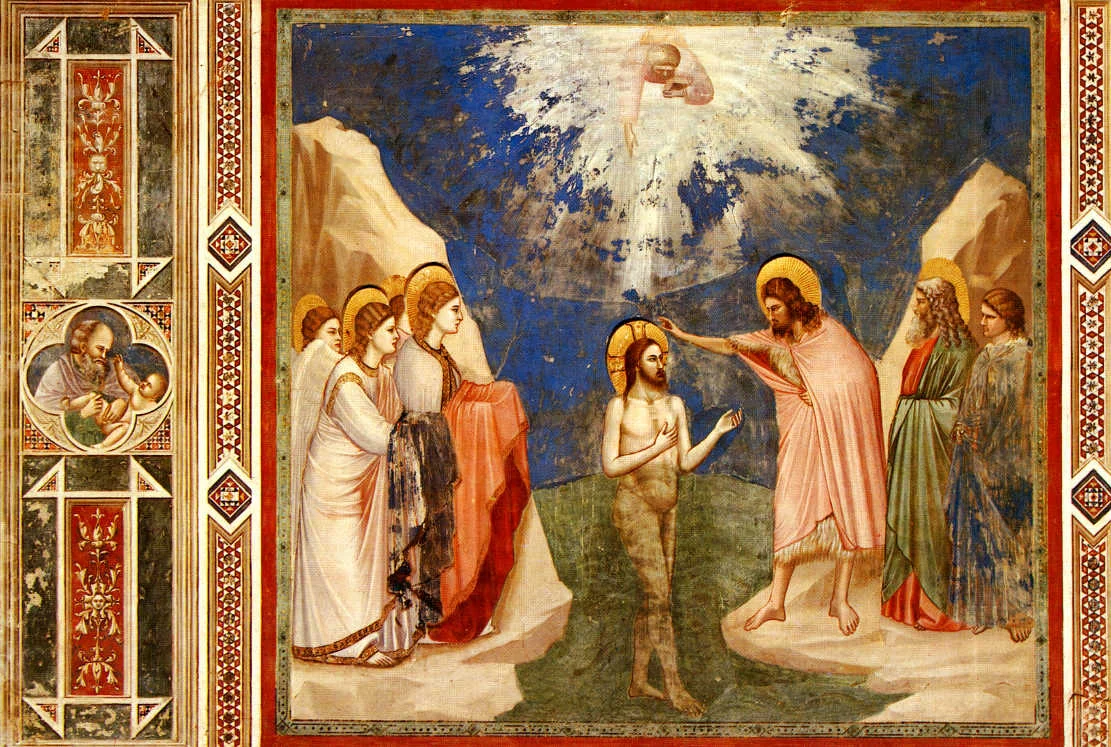

Beyond counter-formation and future orientation, the liturgical calendar of the church serves as a reminder to the people of God of the "temporality" of Christian worship. Especially in the West, we tend to reduce Christianity to an "idea" or a "set of beliefs." Crucially important to the Christian faith is a historicity & temporality that often shakes the comfortably Platonic mind out of the ideal realm of "forms" and into the fleshy world that God created. The "here and now" character of the liturgical calendar reminds us that Jesus came to bring the Kingdom of God to a "here and now" earth. This shapes in the Christian people a desire not to leave this world to its own devices but to see this world changed and that things would be "on earth as it is in heaven. Smith puts it well by saying:

The temporality of Christian worship—macrocosmically expressed in the Christian year, microcosmically expressed in particular elements each Sunday—trains our imagination to be eschatological, looking forward not to the end of the world but to "the end of the world as we know it." (pg. 158)

Church Calendar

In conclusion I want to go back to something I said in the first post of this liturgy series. I made the point that all of life is liturgical. I hope that my analysis (or, rather, James K.A. Smith's!) of the liturgical calendar may start to open this reality up to you readers. We must always be telling ourselves that it is never "whether" but always "which." It is not whether we will have a liturgical calendar that will rule our years, it is which liturgical calendar will rule our years. There are many competing liturgical calendars that are vying for your service.

I for one always feel the pull of the liturgical calendar of college football. Every August through February serves as the high points of this particular liturgical calendar. The "off-season" is even marked by liturgical events of preparation (the spring game, media days, fall camp).

As Christians we should be orienting our lives around the risen Lord who is Lord of all! Let me leave you with a powerful quotation from Smith to hold you over to next Thursday:

We are a stretched people, citizens of a kingdom that is both older and newer than anything offered by "the contemporary." The practices of Christian worship over the liturgical year form in us something of an "old soul" that is perpetually pointed to a future, longing for a coming kingdom, and seeking to be such a stretched people in the [present who are a foretaste of the coming kingdom. (pg. 159)

Food for thought.

Michael