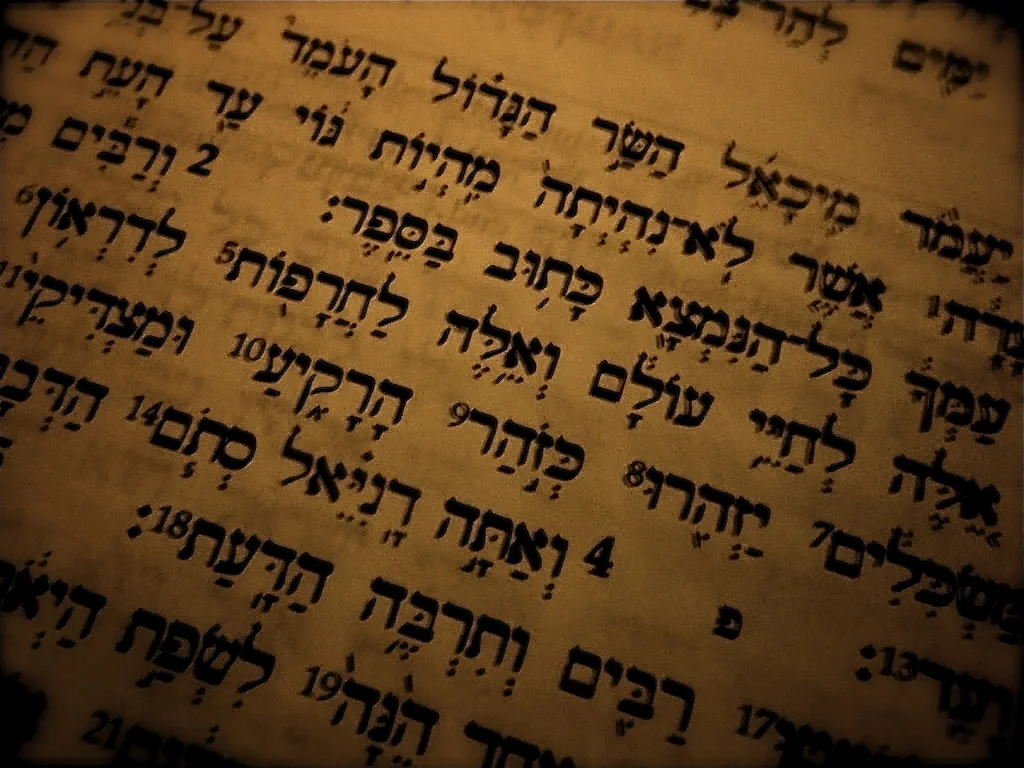

Using Biblical Language in Teaching

One of the top ten questions I get asked as a seminary student is, "Oh, so do you know Greek and Hebrew?" Biblical language is, for many people in many different denominations, an essential part of rigorous pastoral training. So, how can leaders make biblical language pastoral? Disclaimer: I write this article primarily as a seminary student as well as a teacher of Koine Greek. I don't have extensive preaching experience, so take what follows as some thoughts from the academic side of things. With that said, here's three things to consider.

1. Be wary of bible software.

Ok, so I'm definitely not the first person to say this, but here goes: Programs like Logos, Accordance, Bibleworks, and others are really great for reading and studying the Bible. Yay. This is good. However, they are also really great at making you think you know more than you do. Bible software can be a great resource; I use Logos myself. But it isn't a replacement for actually understanding Greek and Hebrew and being able to use that understanding responsibly. One of the ironic dangers is that bible software puts loads of information at your fingertips. This can be a good thing! Access to information is one of the main reasons to use such software! But, if you don't know how to use that information, then it can do more harm than good.

Viewing bible software as a replacement for language study is a bit like buying a travel guide to London, and then acting like you've been there. Word study can be a very helpful feature, but also a very tricky one. Highlight a word and you can pull up entire ranges of meaning that can apply to that particular word! Fantastic. However, it takes some wisdom to understand what meaning works best in context. This is where language study will help you. If you only know enough to be dangerous, you need to know more. And speaking of word study...

2. Don't use the word "literally."

Words don't "literally" mean things. Even the word "literally" doesn't literally mean literally anymore. Thanks, Oxford English Dictionary! That's because the meaning of words depends on usage in context. To provide an example in English, if I say to you, "I'm just dying to see that new Christopher Nolan movie, Interstellar," and you respond by calling an ambulance and administering CPR, you've misunderstood the meaning of what I've said. That is a somewhat ridiculous hypothetical scenario, to be sure, but I hope it illustrates the point. Words do not have meaning that is independent from the way they are used in specific situations.

Where Greek is concerned, a decent amount of homiletic ink has been spilled concerning the different words for "love" that crop up in the New Testament. Agapao, phileo, storge; all of these words mean "love." Some folks will try to say that agape "literally" means a self-sacrificing love that does not expect anything in return, whereas a philia love bears a certain mutuality, a brotherly love, a lá Philadelphia, the city of the same. However, if we try to be thoroughgoing with these sorts of so-called literal distinctions, we run into a problem. For example, in Genesis 34, Dinah, the daughter of Jacob and Leah, is raped by Shechem, a local prince. Immediately after this horrible act, the Greek of the Septuagint translation says that "he loved the young woman and spoke tenderly to her." The word for "love" in this passage is, you guessed it, agapao. A self-sacrificing love? Not so much. This is an extreme example, but it becomes obvious that agapao does not always mean a certain type of sacrificial love; Genesis 34 uses this word to indicate what appears to be a perverse, lust-driven type of love. So if we say that agapao "literally" means this or that type of love, we are most assuredly wrong. Agapao simply means "love"; the sense or force of that love will be determined by context, and not by any "literal" lexical definition. When teaching on love, we should simply speak to the context and teach what Paul or John or whoever it may be is teaching.

Talking about the meaning of words in terms of what they "literally" mean is misleading to our audience; it flattens out the way language works and gives our listeners ideas which are not linguistically appropriate nor pastorally helpful. If words have "literal" meanings, then the Bible is a book to be lexically decoded, rather than a textured work of literature to be appreciated and faithfully translated and interpreted. In short: don't say "literally." Like, literally don't say it. And speaking of not saying things...

3. Maybe don't bring up Greek/Hebrew at all!

If you're working on a sermon or some teaching material and you're wondering whether you should bring some discussion of a Greek or Hebrew word into play, ask yourself this: "Can I make this point another way?" The moment that you mention biblical language in a teaching context, you are inherently differentiating yourself from your audience. To your listeners, you seem to have access to something that they do not; you are reading a different Bible. But that's not really true! Certainly, studying biblical language gives teachers insight into many nuances within the text and the benefits are great! However, the English translations that Joe and Jane Layperson are reading out there in the pews are pretty much right on.

The Reformed tradition has a long history of giving the Bible back to the people in the vernacular, and the preaching and teaching we hear in our churches should inspire confidence in those who hear that what they hold in their hands is the reliable word of God. As a student of biblical language, I don't have any special gnostic-ish linguistic knowledge about God's word! I would never want to give my listeners the impression that because I study Greek and Hebrew I have access to some sort of secret revelation that is off limits to them. My study of Greek and Hebrew informs what I say and how I read the text, but the text I'm reading is not vastly different from the text that is in front of my listeners. Maybe Paul's use of agapao can tell you something about the way in which he views Christian love. Great! Your study has paid off. But is it helpful to mention that linguistic information in your teaching? Maybe not. If I can express what Paul is saying without bringing up Greek, then it will be that much more accessible to the people I'm serving.

Biblical language is a gift; scripture is given to us in very earthy, very human languages, and we have the privilege of listening to God's voice through them. It's a great thing to practice reading scripture well for his glory. We should be encouraged that God has providentially chosen to give us his word in this way and that he has sent his Holy Spirit to encourage us, comfort us, and interpret to us the Word made Flesh.