Liturgy Series: Part 4 – Music

While the church is often described as “a people of the book,” isn’t it the case that throughout it’s history it has also been a people of the hymnbook?

– James K.A. Smith

Welcome to the fourth installment of the “Liturgy Series!” If you’ve missed out on parts one through three then click on the links to catch up (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3). This weeks installment brings us to the ever-popular and debated section of the modern worship service: music. Perhaps no part of the modern church’s liturgy has been more embattled than that of song. While I will offer some thoughts as to the “style” or genre of music in this post I will first (and foremost) speak into the actual event of congregational singing in the worship service of the church. As with the previous posts of this series, I will rely heavily on James K.A. Smith’s work Desiring the Kingdom: Worship, Worldview, and Cultural Formation (“DtK” hereafter), however, I also plan to bring in some helpful input from one of my favorite (and more polarizing) authors: Douglas Wilson.

Formative Song

By this point in the series it should be apparent to you that our concern is with the formative nature of the liturgy. Thus far I’ve argued that liturgy is both unavoidable and formative. By “formative” I have noted that the communal practices of the local church serve to shape and mold the life of it’s congregants. We’ve already looked at the ways in which the “Liturgical Calendar” and the “Call to Worship” shape the people of God by the way their (annual & weekly) calendars are shaped. Today I want to take a closer look at the formative nature of “Song” on the people of God, specifically the formative nature of congregational singing.

One of the primary affects of singing is to remind us that we are “embodied” creatures. All too often in modern forms of Christianity the emphasis is on didactic information. The Christian faith is too readily shrunk down to a “set of beliefs” or a “worldview.” Song reminds us that we are more than just “brains on a stick (as Smith puts it). We are bodies that eat and drink and sing and love. “In song there is a performative affirmation of our embodiment, a marshaling of it for expression—whether beautiful songs of praise or mournful dirges of lament.” (DtK pg. 170)

When the people of God gather to worship and sing they do so as creatures of God’s good creation. The singing of the people of God serves as a reminder of our calling to be “subcreators.” As we are marked with the image of the Creator-God we are called to create. We must not forget that music is a form of creation. “Music and song seem to stand as packed microcosms of what it means to be human. How appropriate, then, for song to be such a primary means for reordering our desires in the context of Christian worship.” (DtK pg. 170)

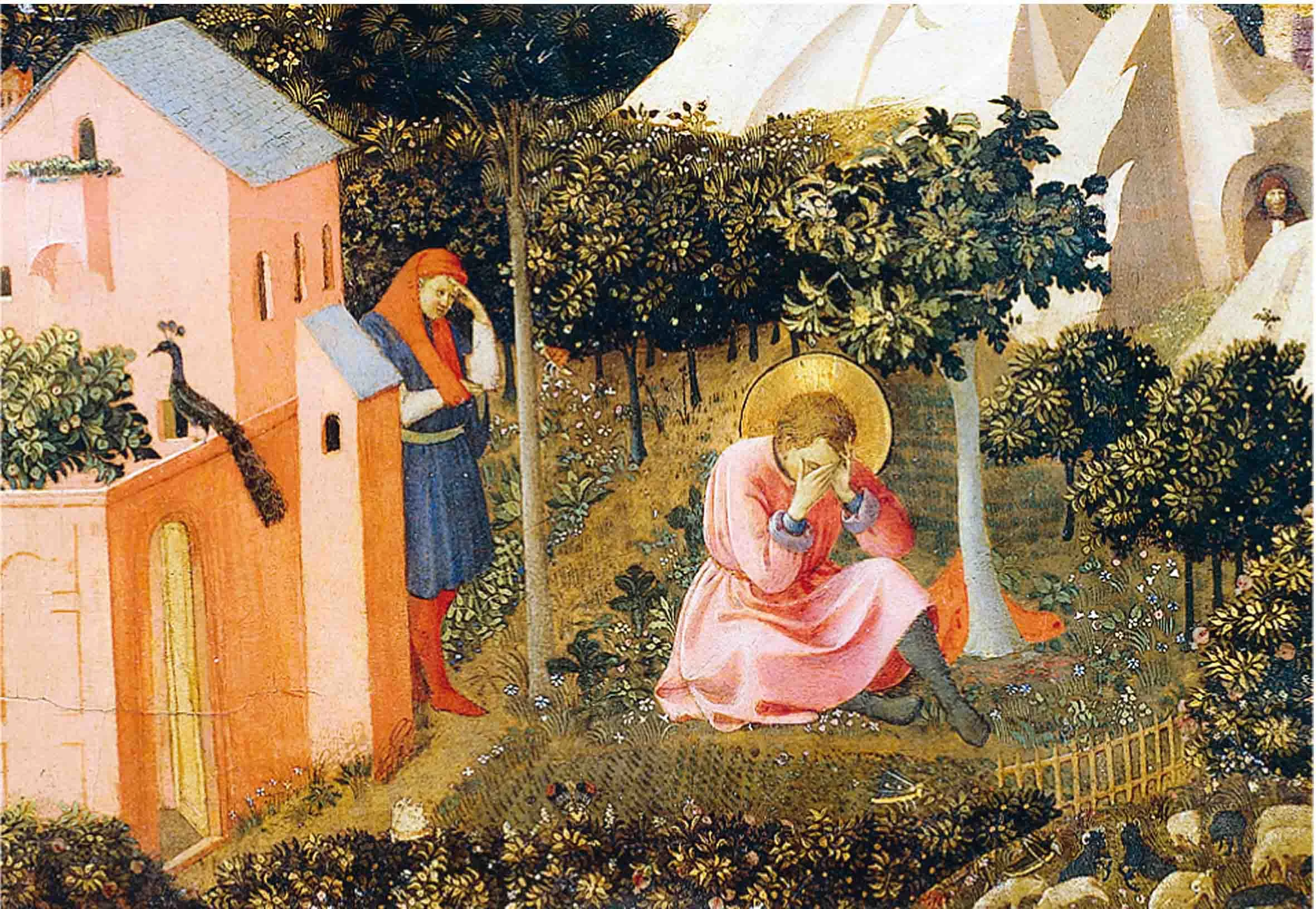

As well as reminding us and encouraging us in our embodiment, song also has a way of shaping the very core of our being. Music shapes us and sticks with us in ways that other forms of “communication” do not. As I’m writing this the band Of Monsters & Men is playing in the background. I first came across the band the summer before Caroline and I got married. I downloaded their album “My Head is an Animal” right before we went on our honeymoon to Breckenridge, Colorado. To this day I am reminded of the rocky mountains and my beautiful bride whenever I hear that album. Music tends to work on us on a level that is “below” the brain; a level that is more in the “gut.” This doesn’t mean that music is anti-intellectual but, rather, that it is “pre-cognitive.” Again Smith puts it well:

[Due to the] cadence and rhyme, partly because of the rhythms of music, song seems to get implanted in us as a mode of bodily memory. Music gets “in” us in ways that other forms of discourse rarely do. A song gets absorbed into our imagination in a way that mere texts rarely do. Indeed, a song can come back to haunt us almost, catching us off guard or welling up within our memories because of situations or contexts that we find ourselves in, then perhaps spilling over into our mouths till we find ourselves humming a tune or quietly singing. The song can invoke a time and a place, even the smells and tastes of a moment. (DtK pg. 171)

When we view music & song in this way it is no longer possible for congregational singing to be taken lightly. Music shapes the corporate body in such a profound way that it cannot be seen as merely a “transitional” time in the worship service or simply a way to attract the “unchurched.” When music merely serves as “transitions” in the service or as an advertisement to get people through the door then that communicates something very important to the congregation about what is happening in their singing (namely: not much).

Appropriate Song

Something that must be understood at this point is that differing types of music will serve for different ends (telos). Because we have seen that music shapes us we know that all music types of music will shapes us in different ways. The Bible makes it clear that different types of music are appropriate for differing circumstances. Douglas Wilson puts it well in his book Mother Kirk: Essays on Church Life:

Music is teleological; it is designed to perform certain functions, to arrive at a certain end. It is not true that any piece of music can be performed for any function, and have the results be at all reasonable or normal. When Saul was in a blue funk, David’s music would soothe him (1 Sam. 16:14–17). When the musicians of the Temple came to prophesy, they did it with musical instruments (1 Chr. 25:1). When certain children wanted a jig, they played a pipe (Mt. 11:17). When the prodigal son returned home, the residents of that household broke out the instruments that were conducive for a good bit of dancing (Lk. 15:25), dancing and music, incidentally, that could be heard down the driveway. (pg. 138-139)

What we see here is that music should fit the occasion. This means that we don’t need to be sticklers about any particular type of genre of music but we do need to seek propriety in the occasion the music is attending. Again Wilson:

The problem with contemporary worship music is not the kind of music it is, but rather the kind of occasion everyone seems to think the service is. (Mother Kirk, pg. 139)

Much of the “contemporary” worship world has a bigger problem with what they think “church” is than they type of music they are playing in church. When we begin to see that the worship service is just that: a worship service, and we begin to take into account who it is we are worshiping: God, then the type of flippant is effeminate worship music that purveys so much of the “contemporary” worship would (quite naturally) fall by the way side. Wilson appropriately cites Hebrews 12:28–29 to give us a little context for what we are doing when we gather as a congregation to worship:

Wherefore we are receiving a kingdom that cannot be moved, let us have grace, whereby we may serve God acceptably with reverence and godly fear: for out God is a consuming fire. (KJV)

When we come together to worship we are receiving a kingdom (the kingdom of God) and we are serving God (we are to do so with reverence and godly fear) a consuming fire.

Conclusion

Like all parts of the liturgy, music is both unavoidable and massively impactful. Whether we like it or not the words and rhythms we sing as a congregation are shaping us into a teleological people (a people facing a certain kingdom). Considering the weight of this proposition we should be increasingly concerned with which kingdom our songs are pointing us. Are the songs we sing as a congregation pointing us inward toward the kingdoms of self? Are they simply worldly songs painted over with a Christian veneer? Or are they robust anthems that direct our hearts toward the king Jesus? Hopefully they are the latter, because it is these robust anthems of longing and faith that serve (as Wilson puts it) as battering rams toward the gates of Hell.

Food for thought.

Michael